Last May 30, police personnel from the Third Police Station in Chaco violently entered, without a search warrant, the home of a family from the Qom community, located in the Banderas Argentinas neighborhood, in the town of Fontana. Then they beat those who were inside the house, among whom were women, youth and minors. Thanks to the fact that several members filmed what happened, the event went viral on social networks and removed the police officers from their position.

”

Criminalization of aboriginal peoples has not stopped

. That people have cell phones and can record you, has made them take a little more care in some places. There is greater visibility and more media complaints, “explains Rosita Sidasmed, coordinator of the NEA of the

National Aboriginal Pastoral Team (Endepa)

.

Several cases of discrimination against Aboriginal families living in the housing complex called Gran Toba, located in the northeast area of Resistencia, and one of the largest sources of contagion in the province, were also recorded. They blame them for “having brought” the coronavirus.

Specialists and members of these towns, agree that this

It is a daily practice and extended throughout the Argentine territory

. According to a 2018 Endepa report, “institutional violence weighs on indigenous communities and has increased in recent years. It is clearly observed in the national and provincial state agencies, but particularly in the judicial system.”

What is the sustenance of this systematic violation of rights directed towards the native peoples? What prejudices sustain it? How is it done to narrow that cultural gap that only deepens inequality?

In a recent interview in LA NACION, Victoria Donda

, the current auditor of the

National Institute against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism (Inadi)

, pointed out that the matrix behind certain practices installed not only in society but also within the Argentine State, is the same:

a structural racism, present from our beginnings as a nation.

“It costs a lot to be able to take charge of Creole racism and that is why it is not so visible in public policies either. Public policies cannot be elaborated thinking that we are all the same because we are not, because there are others,” he said.

Asked, specifically, for the aggression suffered by the Qom family in Chaco, Donda assured that it is a consequence of structural racism towards “the native peoples and in those places where the native peoples and the descendants of those original communities are the majority, majority who later it is not reflected in the places of power. ”

They are stigmatized as rough, violent, lazy, wild, and dangerous. All these negative connotations towards native peoples are part of the social view.

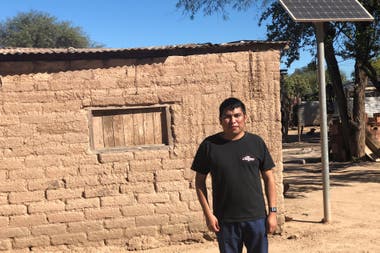

“Most say that we are incapable. I believe that every human being has the same capacities, that everything is learned, that we have to be included, not excluded,” says convinced Omar Gutiérrez, a 26-year-old young man who was born in Misión Chaqueña, a Wichi community of Salta.

“They discriminate against us due to the physiognomy, the color of the skin and the public force is abused. A policeman comes, without a judicial order, he points a finger at us and they take us to the police station. And we go. so that our rights are respected, “he adds.

Daniel Martínez, a young man from the Wichi community on Lot 44, 8 kilometers from Miraflores, is also afraid of the security forces. “If you go for a walk, the police arrest you, they blame you for many things and they do paperwork for you. We cannot defend ourselves because they have power,” he explains under a tree, in a clearing in the bush where he lives with eight members of his family.

He is studying for a bilbingüe teacher in Juan José Castelli and goes every day on a motorcycle, if the destroyed roads allow it. “If you are going to ask for help, they don’t give you a ball directly. Afterwards they treat you as lazy and croto but they crowd in the stalls,” he claims.

The most forgotten

Dominga Palavecino is 23 years old and has a look of fire. His brow fills a pain that he prefers to scream with his pupils. He is Wichi and lives in Lot 63, in Miraflores, at the door of the Impenetrable Chaqueño, along with his three brothers. She speaks with the body, with indifference and with those jet eyes that transmit a penetrating indignation against the representatives of the “white world”, because they are the faces of oppression, massacres and abuses. Because they stole from their ancestors and their parents.

“They let them die,” says Luciano Palavecino in almost inaudible Spanish, the 25-year-old older brother, when he refers to the last days of his mother with tuberculosis and his father with Mal de Chagas. Their complaint is that they were not treated properly in the hospital or given an explanation of what had happened to them.

The Wichi, as well as the rest of the original peoples in Argentina, are one of the most neglected populations and suffer different forms of violence by the State and society in general.

A systematic distraction, endured from generation to generation, is the one that was building a primitive distrust that grows every day.

The gap is economic, social, educational and health, but it is essentially cultural.

They are two worldviews that collide permanently. “The ancestors put him

ahatay

the white man, which means devil or demon after the great massacres that took place, “explains Gutiérrez.

Although their rights are recognized in the National Constitution, sometimes they do not even exist in statistics. It is estimated that in Argentina there are close to a million people from indigenous peoples, but when living in remote areas, in some cases the production of data itself does not reach their spaces. “They are not always included in the census and other measurements, their gaze does not appear and that contributes to making their problems invisible,” says Carolina Aulicino, Public Policy Officer at

Unicef

.

Dominga only communicates with her brothers. He doesn’t even do it with school teachers. He can read and write in Spanish, in a round, neat and fluffy cursive letter. It is not that he does not speak because he does not understand. He does not speak because he does not want to. Because she is afraid, because she is angry, because she does not want to cross a world that is not her own, that manages other rules and other values.

When thinking about public policies that manage to give them a decent life, it is essential to deepen and repair this historical wound.

Otherwise, they will never be successful. How can we settle this? “Governments have a lot of discourse regarding indigenous policy but very little application,” says Sidasmed.

They speak Spanish half-heartedly, live in isolated areas, in precarious conditions, are not used to associating with institutions and have very limited access to justice. All these condiments make them especially vulnerable to abuse and abuse by the Creoles.

Examples there are hundreds. Like the one that occurred in early May in Salta, where

a group of club leaders who kept the amount of the Emergency Family Income (IFE) from indigenous families located around the town of Embarcation in Salta

. Even cases were detected in which this group of scammers, in addition to withholding the money, forced the victims to perform unpaid work under the threat of taking the IFE from them. “Aboriginal communities are at the mercy of political leaders, who take money from them and enrich themselves,” the head of the Salta Fiscal Unit, Eduardo Villalba, told LA NACION.

All Luisa Acosta wants is for it to rain so that she can water her garden and give her animals water, and that the politicians leave them alone. He lives in Lot 63, in Miraflores, along with 25 people from his family. They have a chapel and a school of their own where an adult-level teacher teaches them to read and write. Faustino Acosta is one of the litter of young people who does the heaviest jobs. As he has Mal de Chagas, he walks a few meters and is already agitated.

They are tired of asking the municipality to install the electricity and water service. “Politicians always come to lie just. They promise us light, drinking water and housing if we vote for them, but they are all verses. I know the politician and I don’t want to know anything about them because I don’t trust,” says Faustino, with tears in his eyes.

The indigenous peoples lack everything: electricity, water, bathing, work, food and productive land.

The hard data dehumanizes this reality that only becomes meat when some news appears in the media about deaths from malnutrition. According to Unicef, 23.5% of indigenous households meet unsatisfied basic needs (UBN), compared to 13.8% of non-indigenous households. The provinces with the highest levels of UBN in indigenous households are Formosa (74.9%), Chaco (66.5%) and Salta (57.4%).

“They are one of the populations most crossed by multidimensional poverty and most neglected. There are many geographic, educational, economic and language gaps that make it very difficult for these populations to reach the cities. And what is clear is that it is the State that has to approach them to ensure their rights, “says Aulicino.

The situation is critical. But it is not enough just to build houses, install cisterns or sanction intercultural bilingual education.

Indigenous peoples need to be part of the conversation, consulted on the best answers to their demands, and their culture is respected when implementing them.

“Non-indigenous people usually say ‘they have stayed in time’ and we want them to progress. But what is progress for them? It is not linked to material things but to being in balance with nature. If they are sick, have the possibility of going to the mountains and getting their natural medicine. For them, the most important thing is good living, which has to do with the quality of their relationships and harmony with nature and the environment, “reinforces Sidasmed.

Language, an obstacle

The Wichi are a closed town, with little physical contact between them, of few words, who value the word and are very reluctant to interact with people outside their community. “Also when we speak we include signs to understand each other. In general we are afraid to speak and that they do not understand what we are trying to say,” explains Guitiérrez.

One of the main problems for integration is language. Many of the adults in these families speak only Wichi and find it impossible to interact in public institutions without a translator.

“It would help a lot to have translators in hospitals, in police stations or in the civil registry. They are undocumented or they write them down badly and they don’t realize it,” says Lucrecia Hernández, aboriginal teaching assistant at School No. 1034 Lot 76 in Miraflores.

Thanks to the implementation of bilingual intercultural education, children and young people learn Spanish and preserve their language. At the Hernández school, Wichi students have a bilingual aide from kindergarten through fourth grade.

“The boys take a long time to incorporate Spanish because at home they do not speak it. They have a hard time letting go and even more so if it is with a Creole. Many finish school without expressing themselves well in Spanish, without being able to explain what they want or need. before a public institution or before the rulers who can help them, “says Hernández.

The territory in danger

Why are the Wichi in permanent territorial and food emergency? It is a response that has several edges. What is clear is that attempts by the State to reach these communities have been insufficient and have failed. These families continue to fall on the margins of a system that is not intended for them or for their idiosyncrasy.

Most of the indigenous peoples live in isolated rural areas, far from the big cities. In El Impenetrable, for example, families always lived from the bush, hunting, fishing and growing food in small gardens. The women, for their part, search for it by making crafts in chaguar that end up selling for a few pesos.

But in recent years, the explosion of the authorizations for clearing and forest exploitation and the loss of the territory, put the community balance at risk. According to Endepa data, the surface dismantled during 2017 in the provinces of Salta, Santiago del Estero, Formosa and Chaco was 128,217 hectares. Almost half deforestation occurred in protected forests.

“The dams are dry because it does not rain because of all the clearing they are doing. It is not verified if the trucks have the proper papers, because you can remove trees but later you have to reforest. And that does not happen. it forbids him to cut a palo santo because it is a protected wood and they are taking truckloads of palo santo to other places, “complains Adriana Cragnolini, director of School No. 1034 Lot 76 in Miraflores.

The loss or degradation of the forest for them is equivalent to death. Because it is there where they meet, exchange, transmit their culture, taking advantage of natural assets, and language, among others. Law 26,160, which contemplates the emergency in terms of possession and ownership of the lands traditionally occupied by the indigenous communities originating in the country, was passed in 2006 and has already had four extensions.

“It is the one that provides for the survey of the territories. As of today, only 38% of the communities have completed the territorial survey. This is extremely serious because the most important thing for an indigenous people is the territory, which is a giver of identity and when they don’t have it their worldview is hurt. The creoles wonder why they want the land if they don’t produce it and the indigenous people answer that the land is their mother, there they find food, medicine and take care of the ecosystem, “adds Sidasmed .

With their main source of food and work reduced to a minimum, these families do not find work alternatives to survive and they have to depend, almost exclusively, on state assistance.

“All the indigenous people have some social benefit. There are attempts at cooperatives of bricks, handicrafts, and animals, but that competes with provincial pensions to be the labor of the politicians on duty. When some formal work comes, young people cannot access because they charge a fictitious disability grant. It’s like a trap, “says Sidasmed with concern.

Not everything is lost. There are many experiences of articulation with indigenous peoples that are successful. It takes time to repair the wound but it is possible. “I no longer live that situation of mistrust personally. I have been working with them for 22 years and I believe that we must rescue what indigenous peoples give us. In these times of pandemic, for example, learning about their way of life, their care to nature and its territories and its way of relating to the cosmos, “concludes Sidasmed.

.

Publicado en el diario La Nación