Fuerte Apache es un vecindario ubicado en la periferia de Buenos Aires, Argentina, que ha sido conocido históricamente por su alta tasa de delincuencia y violencia. Sin embargo, esta percepción negativa es en gran parte injusta y se ha basado en estigmas y prejuicios infundados. En este artículo, exploraremos la realidad detrás del mal llamado Fuerte Apache y analizaremos los estigmas asociados con este vecindario.

¿Qué es Fuerte Apache?

Fuerte Apache es un vecindario ubicado en la periferia de Buenos Aires, Argentina, que se hizo famoso por su alta tasa de delincuencia y violencia en la década de 1990. El vecindario fue nombrado después de un fuerte militar que solía estar en la zona. En la actualidad, Fuerte Apache es el hogar de más de 80.000 personas de bajos ingresos.

Estigmas asociados con Fuerte Apache

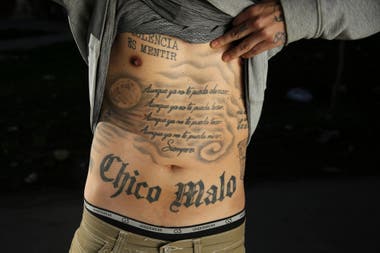

Durante mucho tiempo, Fuerte Apache ha sido considerado un vecindario peligroso y violento, con altas tasas de delincuencia, drogadicción y violencia doméstica. Sin embargo, esta percepción es en gran parte infundada y está basada en estereotipos y prejuicios. En realidad, la mayoría de los residentes de Fuerte Apache son personas trabajadoras y honestas que simplemente buscan un lugar para vivir.

La lucha contra los estigmas

A pesar de los estigmas asociados con Fuerte Apache, hay muchas organizaciones y personas que trabajan duro para cambiar la percepción del vecindario y mejorar la calidad de vida de sus residentes. Desde organizaciones comunitarias hasta grupos religiosos y vecinos individuales, hay muchos que están trabajando juntos para construir un vecindario más seguro y unido.

Conclusión

En resumen, Fuerte Apache es un vecindario que ha sido injustamente estigmatizado debido a su historia y a prejuicios infundados. Aunque es cierto que el vecindario ha enfrentado desafíos, la mayoría de sus residentes son personas honestas y trabajadoras que simplemente buscan un lugar para vivir. Es importante reconocer los estigmas asociados con Fuerte Apache y trabajar juntos para crear un vecindario más seguro y unido.